Whether it's his punk and noise bands Big Black and Shellac, his work as an audio engineer for bands such as Nirvana, Sunn O))), The Breeders, PJ Harvey and Pixies or his vision for major labels, Steve Albini has left his mark. on the underground music scene. Especially for an engineer who says he doesn't do anything except put down microphones and connect gear (a 'producer' with an opinion would be out of the question), he has a long list of legendary records to his name. Is there really nothing Albini does to make a band perform at its best?

Written by: Jasper Boogaard

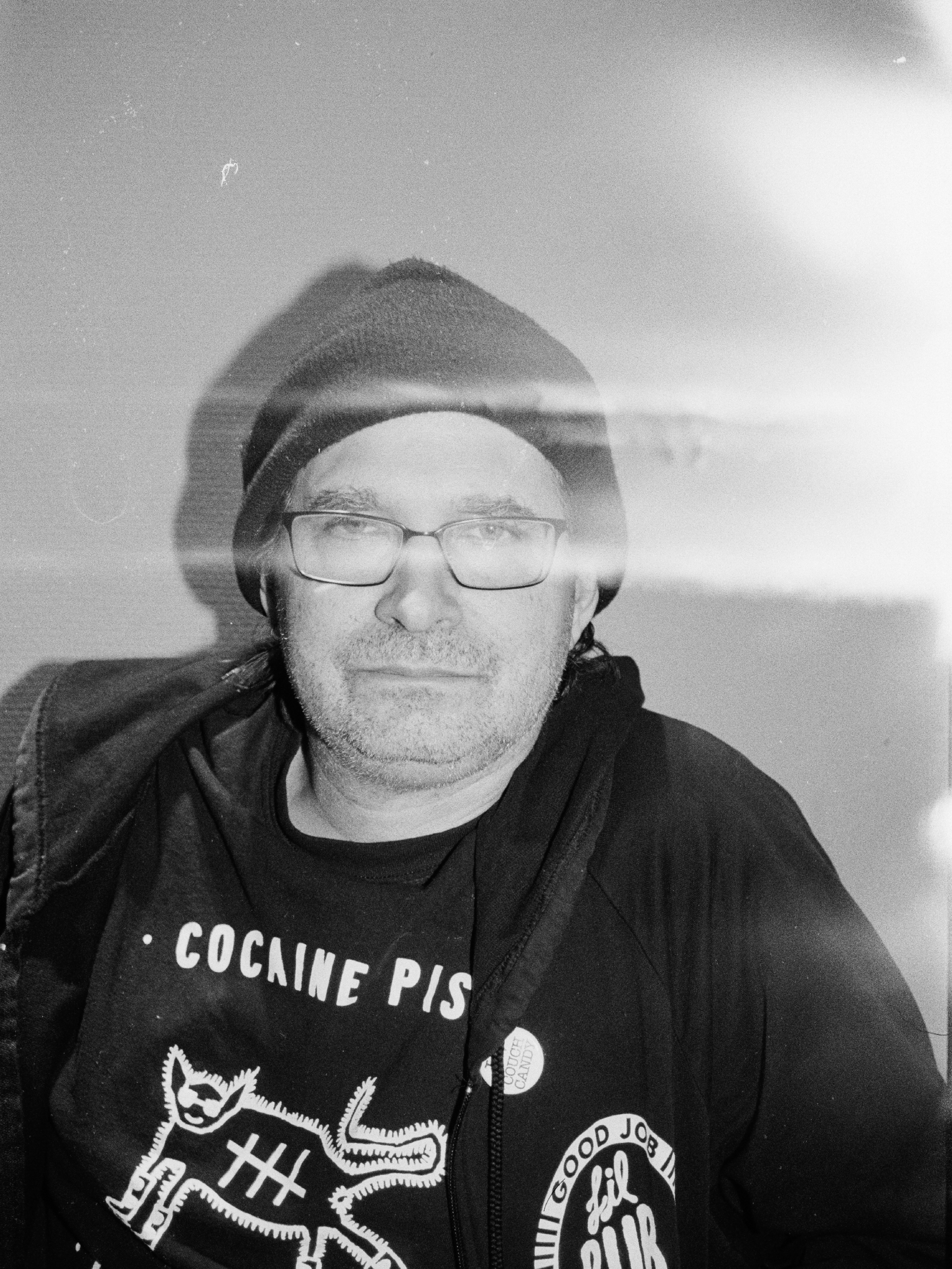

Photos: Cheong Park

During the busy tour schedule of his band Shellac, Albini manages to make some time for an interview. In the somewhat gloomy Ibis Business hotel in The Hague, he talks about his career as an audio engineer, spanning more than forty years.

Albini's start as an engineer is a story he shares with many of his colleagues. “I was always in bands as a teenager. And if you play in bands you quickly end up in a scene with all your friends who are also in bands. At that time it was difficult to get a recording.” Out of necessity for the bands in which he plays, he started working himself in the late 1970s. “In every group of friends there was one person who took on the task of learning how to record. I was that person in my group of friends. So I started recording my own bands, friends' bands and friends' bands. It was all very informal with no commercial pursuit, just to make sure everyone had a recording of their band.”

“It was a brutal trial by fire. Either it worked and everything was fine, or it didn't work at all and it was horrible.”

Learning how to record a band was very different from today: “The biggest problem was the equipment. A tape recorder cost many thousands of dollars, so the way me and my friends did it was this: I rented a 4-track tape recorder and some microphones, and got to work on that.” That was not always easy. “It was a brutal trial by fire. Either it worked and everything was fine, or it didn't work at all and it was horrible.” Gradually he expands his skill set. “I came across very few professional engineers, but when I did see them, I questioned them.”

He also devours books on recording techniques. First at the public library, then at Northwestern University, where he studies journalism at the same time. With that study he ended up not doing much more than the fanzines, an important part of the underground scene, for which he wrote at the time. “Fanzines were the only way to get information about the underground. There were some sympathetic radio shows, but most of the information was word of mouth through people you met. The fanzines, which were kind of an outgrowth of your social circle, were very important for me to discover new music and meet people. It was like a guide: if the fanzine wrote about good music, you called the writer and asked what the cool clubs were to play. They could then tell you who the promoter of that place was.” Albini also mentions record stores as an important role for the infrastructure. “In every city the record store was a kind of cultural center. In Chicago it was Wax Trax! Records, that was where all the punks and musicians were hanging out. There were always flyers about new bands, or bands looking for a bassist, that sort of thing. You got a lot of your information from there.”

Albini gains a reputation as an engineer. He is someone who records the band as they perform his material live, who uses large rooms with a lot of reverberation for a big sound and avoids digital reverb in the post-processing as much as possible. It results in a raw sound, as if you are standing right in front of the band. And one thing is central: the engineer has no opinion. “I hardly ever form an opinion about the music I record, because I think that kind of judgment can be distracting and even intimidating for the artist. If the artist has the feeling that I am assessing their performance and professionalism from the control room, it can cause unnecessary stress. In addition, the artist has the most intimate relationship with and knowledge of his music.” Albini sees himself completely as a facility: even if a band wants to copy the exact same sound from a certain record, he's fine with that. “It makes sense that if someone is a fan of a certain sound, they want to implement that in their music.”

"It's hard to imagine that there will be many big studios in the future, because it's not a profitable business. Every year we have to evaluate whether we can keep it up."

From that perspective it is also logical that Albini prefers not to call himself a producer. Especially in the time when he started, the producers were hired by the label, and they also pushed certain creative choices. And he hates (major) labels so much that he previously indicated that Sonic Youth should be ashamed of the fact that they signed a contract with Geffen Records in 1990. This principle seems to be an important part of his personality, but it also hinders him financially: he does not want to receive royalties from the albums he records (“I would like to be paid like a plumber. I do the job and you pay me for what it's worth,” Albini wrote in a fax to Nirvana at the time), but with even a small percentage of In Utero's sales, he could have had a decent income stream. That doesn't make it any easier to keep a large studio like his Electrical Audio, the Chicago studio he founded in 1997, running. “The costs of a professional studio with trained staff, good equipment and maintenance, and having a large location are very high, and the money coming in from clients has actually decreased over the years. It is hard to imagine that there will be many big studios in the future because it is not a profitable business. Every year we have to evaluate whether we can still keep it up.”

The fact that he does and has such little say in creative input makes the list of legendary albums that Albini has contributed to extra special. As an artist, the best time to hit the studio with him seems to be when you're at your peak as a live band. Is that enough to make a fantastic record? Then Albini is your man. Because when it comes to technically recording that record, Albini is a master and the fact that he does nothing more than that is probably also the silent strength of his discography.

Even though he mainly played Scrabble on Facebook during the recording of Cloud Nothings' Attack on Memory, it remains their best sounding record. And even though Jawbreaker's 24 Hour Revenge Therapy only lasted a few days and all Albini could remember is an annoying hum coming from the guitar amp at one point, it remains their best sounding record. Steve Albini knows exactly how to record a band and if the band knows exactly how they want to shape their record, that can be enough to make a Surfer Rosa or In Utero.

Editor's note: this article was originally published in Dutch. Some quotes may have been altered in the translation.