A year and a half ago, as the world came to a sudden standstill and daily life turned into a slow and uneventful ordeal, Front editor Ruben van Dijk found himself looking for music that captured exactly that. Now, as life is slowly inching towards relative normalcy, he reflects on the sounds that helped him reconcile with all-encompassing nothingness and mind-numbing isolation by highlighting the artists responsible: Green-House, Ben Seretan and Elori Saxl.

Written by: Ruben van Dijk

Illustration: Linde Helene

Looking back at the first COVID lockdown, somewhere between March and June of 2020, I can scarcely remember how I spent my time. I think even then, in the evening, I had probably already forgotten the events of that particular day. There was so much emphasis at the time on how ‘historic’ this would turn out to be, how we would still tell our (grand)children about this. Meanwhile I found myself in some sort of memory vacuum. WouldI tell my children about this someday? What even was there to tell?

Those first few months were pretty much a void. It’s almost blissful in hindsight: nobody was doing anything, so it felt totally OK and acceptable to do nothing. I didn’t pick up a hobby; I didn’t learn a language; I have no new skills to show for from that time; I didn’t even read a single book. What we felt at the time would be a watershed moment, a big reset, that would allow us to change our ways for the better, turned out to just be a passing fancy. At least for me.

The only thing I did acquire was a renewed appreciation for ambient music, something I have carried with me since; something that not only enhanced the early pandemic nothingness, but helped me heal during the much more difficult period that would follow. After a brief summer in which the pandemic already felt like something of the past, long forgotten, the second lockdown (that started in October and only just ended) was a different challenge altogether. As I write this, we, as a society, are slowly but steadily working our way out of that darkness. And much in the same vein, I am working hard to leave my depression behind, finally finding the words to address what’s happened and give meaning to the sounds that have gotten me through.

Over the course of a month, I corresponded with some of the artists responsible for my favourite ambient music of this year: Ben Seretan, Elori Saxl en Green-House. Each of their latest albums helped me reconcile with a very difficult time in my life, all in a very distinct way. I asked them all more or less the same questions: what state of mind did their abstract sounds emerge from? What part did their natural environment play in the process? And was making these albums as therapeutic and healing as listening to them was for me?

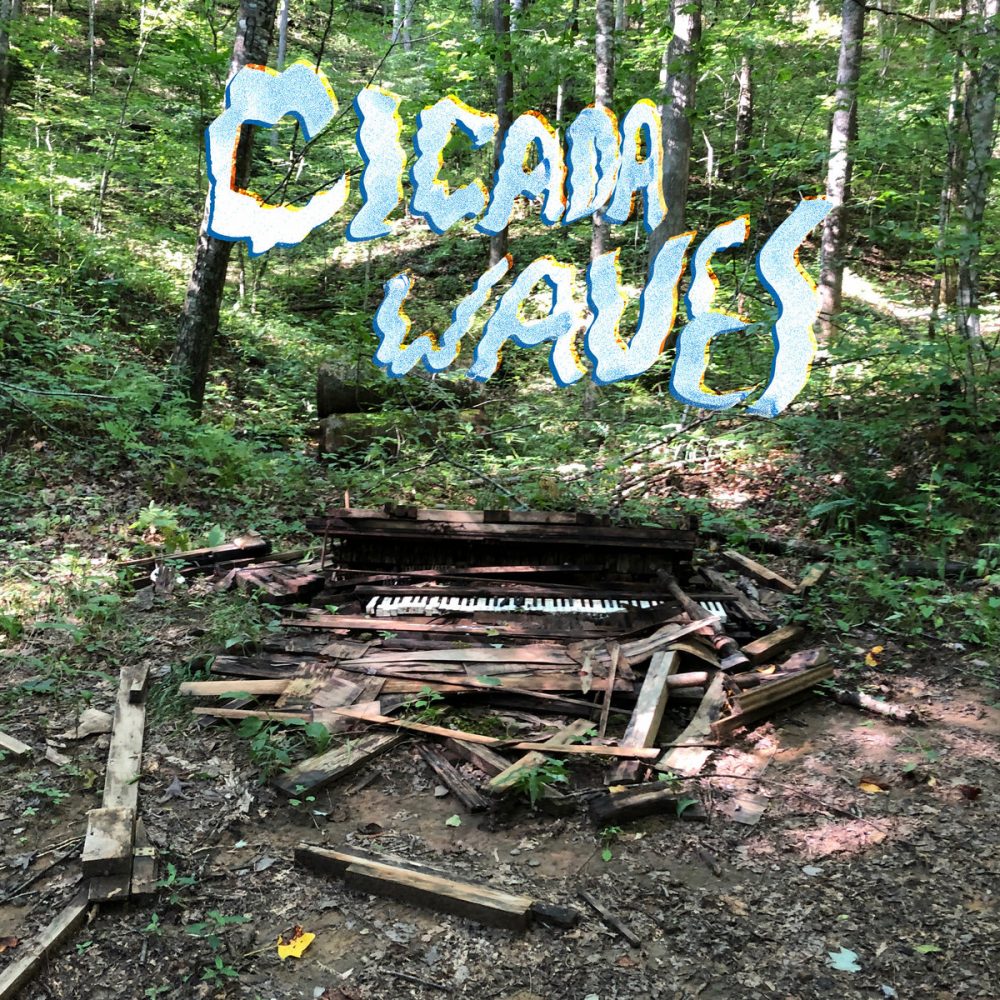

1. Ben Seretan – Cicada Waves

I think I giggled a little, the first time I heard a song from Ben Seretan’s Cicada Waves. ‘Fog Rolls Out Rabun Gap’ it was called, and I found myself mesmerized soon after by how something could be so straightforward and mystical at the same time. What I was witnessing, albeit in an aural form, was, indeed, fog rolling out of Rabun Gap, Georgia, accompanied by a natural orchestra of cicadas, birds and rain, and some guy playing the piano in a very precious but almost absent-minded manner. It was the kind of ambient I had dipped my toes in before – I’m very fond of Yuichiro Fujimoto’s Mountain Record, a mostly acoustic record with the sounds of birds, trains and kids in playgrounds sprinkled throughout – but the utter simplicity and the emphasis on nature of Cicada Waves startled me. A piece like ‘11pm Sudden Thunderstorm’ is so sparse, you could almost replicate the experience by going to a nearby forest on sultry summer night yourself, waiting for the weather to turn. But the word ‘almost’ does a lot of heavy lifting there; it’s precisely the fact that Seretan captured these moments – all of them improvised – the way he did, that makes them so remarkable.

<emCicada Waves is very much a lockdown record, recorded in a time of immense anxiety and isolation, wherein the all-encompassing gravity of the situation worldwide formed a stark contrast with the vacancy that had taken hold of the daily lives of so many people. The moments on this album that resonate with me most, are those quiet moments where you can hear Seretan taking his place behind his piano; a brief instance of intent and purpose that dissipates as soon as the first notes are played and the choir of cicadas becomes an ever louder presence

It’s exactly how many of those initial lockdown days felt; plans and ideas swallowed up, reduced to an elusive state of mind, entirely in the moment and simultaneously nowhere at all. When Cicada Waves came out, in late April of this year, the Netherlands was still very much in lockdown, with a 10pm curfew having just been lifted. That blissful purposelessness of the first lockdown had slowly passed over time, and the inherent societal pressure to do, to be productive had creeped its way into my consciousness once again, haunting me, even though the state of things was all but stimulating any creativity. Walking through my neighbourhood at night, for the first time in forever, listening to Cicada Waves, I felt more present than I had felt in months. I was just somewhere, with nothing on my mind.

Can you take me to the place where Cicada Waveswas recorded? What was the setting like and how do you think it may have seeped into your music?

“I recorded Cicada Waves almost accidentally while I had the lucky opportunity to stay in a dance studio without any internet connection at the foot of the Appalachian Mountains at the north end of Georgia. It was both the quietest place I had been in years and one of the loudest. Quiet in that there were no trains going by, hardly any cars, none of the anthropocentric bustle of New York City where I had been living for the ten years previous to making this record. And loud in the sense that there were just so many other, unfamiliar noises, the biblical buzzing of cicadas among them. I think the tension between peace, quiet, and the calamity of a less human-centred place is really present in the music. That tension is also there in the recording setup - how the 100-year-old baby grand piano got to that remote corner of the world in perfect playing condition I don't think I'll ever fully understand. It was such a beautiful, pristine, man-made instrument out among these rolling thunderstorms and hooting wrens. Didn't take much to find something wonderful in that poetic juxtaposition - I simply pointed my field recorder at the windows and let the chords unfurl.”

You deliberately isolated yourself completely for two weeks. What were you hoping to achieve in these two weeks, going into this? And were you surprised by the outcome?

“It was funny to me at the time to go from a period of nearly total social isolation during COVID into a period of time where I was even more isolated. What a foolish thing to do while I was bemoaning not being able to hug my friends! But I found that I was able to be much more present with my fondness for those people, and for my desire to be close to them. I really felt how badly I missed the world, which is hard to do when the Internet is full of cheap imitations of the real thing.”

“I had big plans for those two weeks - I wanted to write a ton of new songs, I wanted to finish a second series of 24-hour recordings, I wanted to run five miles every day. But instead I spent a lot of my time hypnotizing myself with the piano and reading science fiction and swimming with my buddy Jeff. Almost as an afterthought I captured these sleepy piano improvisations, thinking that I could edit or ‘do something’ with them later. But when I listened back a few weeks after getting home I knew the work was already done!”

Was it a healing or therapeutic experience for you as well, making the album?

“Playing the piano has always been a therapeutic exercise for me. Or I should say: it's soothing for me anytime I let myself play the piano intuitively, without sheet music or ‘trying too hard’ to do anything. I hated learning finger positions and sight reading and things of that nature all through the time in my life when I was being taught the right way to do things.”

“The type of playing I do on this record really started years ago when I had a job managing a fancy movie theater in NYC. There'd be classical music performances on the weekends and for those they'd roll out this gorgeous and enormous grand piano from behind the screen - the rest of the time it sat dormant, and I learned to sneak back there during screenings and play quietly so as to not disturb the movies. I was always listening to what was happening beyond the double doors of the piano room, making sure to notice when the quiet parts might bring attention to what I was playing. Listening beyond the projector-lit screen of the theater, playing soft lines in the dark.”

“But I do think this album was particularly therapeutic. I lived my life at an aggressively maxed out pace before COVID, always doing the most and cramming everything I possibly could into every single day. The pandemic changed all that, of course, and I never really let myself sit with the weight of it until I made these recordings.”

You went to the Appalachian Mountains thinking you’d be playing the piano, but the piano ended up just being one artificial instrument in an orchestra of mostly natural sounds. Making Cicada Waves, what did you learn about composing and the relation between your playing and the environment?

“For a moment I really thought you were going to say "but the piano ended up playing you." Which is funny, but also surprisingly accurate. Playing and recording in that really extraordinary setting was a really effective demonstration of a simple concept: if something wonderful is already happening, it's okay to have nothing to add. My tendency in general is to do too much - I play too many notes, I invite too many people on stage to play in the band, I overshare, I send too many emails. There can be so much power in doing less.”

You’re also a singer-songwriter. What does (making) ambient music give you that more structured, more conventional and lyrical forms of music don’t? “It really comes down to freedom, surprise, and room to spread out. I've always been interested in figuring out exactly just how little a song needs to hold together as a song - a lot of my songs have lyrics that are one phrase repeated ad nauseum, or even one word (‘Ticonderoga’ off of my first solo LP has a lyric exactly one word long and runs over seven minutes in length).”

“By most definitions a song requires a series of changes - chords need to change, words need to progress or tell a story, there needs to be a verse and a chorus and maybe a bridge. Even the most outré definitions of what qualifies as a song would seemingly require some change. But ambient music - and I sometimes struggle to use that term - gives you permission to not change, to hold stasis, to feel yourself changing in relation to something that is constant. That's really what I love about it.”

Are there specific moments in which you are drawn more to ambient and moments in which you are drawn more to songwriting? (Whether you’re making it yourself or just listening to it.)

“I've noticed a funny thing about my listening habits over the last year, which is that my appetite for lyrics and songs in general increases as the day goes by - in the morning, I'm obsessed with this idea of keeping the day full of possibilities, which means that I refuse to look at my phone for at least an hour or two for fear that an email or a text will force me to think too specifically about what the day might hold. And I think songs and music with lyrics are a part of that - words feel very ‘locked in’ to at least a set of meanings. But by the time dinner rolls around I am usually hungry for conversation and communion with others so I am more than happy to throw on hokey country or Sade, et cetera. That's when I want to hear words. It used to be that I could also listen to ambient music while I was writing but now I find that totally impossible

"I can only write in total musical silence, like I'm doing right now, haha!”

For me, my love for ambient music was enhanced by the first lockdown last year, when the lack of structure, the quiet intensity and the spaciousness of it all suddenly aligned with my day-to-day life. I’m curious as to whether you experienced ambient music differently this last year; and also, if there was a specific moment or experience you remember that made you fall in love with ambient music? “I think I experienced all media differently this year - certainly watched more TV than I have since I was a kid (Star Trek, mostly), I've been reading constantly and at a wild clip, and my listening habits have changed tremendously. When I was really scared and anxious living in NYC I found ambient-type music to be actually really difficult to listen to - washy, instrumental music can be heard in a lot of different ways and while I was freaking out about this plague descending on my life anything too bleary just sounded like the fog of fear in the air.”

“I've been interested in ambient music for a long time, but one moment really sticks out to me as a possible origin for wanting to make it: one summer in college I stayed on campus and got a gig mowing a professor's back lawn while she was away. The second or third time I mowed her lawn I put on Four Violins by Tony Conrad which, if you haven't heard it, is just this huge stack of noisy, scratching, sometimes in tune violins totally bleached out and blasted to maximum volume. It's certainly not gentle ambient music, but it is one sustained chord for at least a half an hour, and listening to that on my headphones mixed with the smell of gasoline and cut grass and the two-stroke violence of the lawn mower and the sweat of the Connecticut sun... it totally stirred my brain around, just stuck it in the paint mixer and left me feeling like I had seen behind the veil of reality, like I had stepped in God's chewing gum.”

Finally: are there any ambient records that have impacted you or have had a healing effect on you, that you would like to recommend?

“Well, I just recommended Four Violins, but here are some faves from this year: Potential Landscapes by Tristan Kasten-Krause, Futurangelics by Brin, Dntel, More Eaze; Royal Blue by Rhucle. Also I think A Rainbow in Curved Air (by Terry Riley, ed.) might be one of my favorite instrumental / ambient records of all time.”

2. Elori Saxl – The Blue of Distance

For a long time, and often still, I tend to seek out ambient records that soothe me, make me feel more comfortable, relax the mind rather than trigger it. So when I caught myself coming back to The Blue of Distance by American composer Elori Saxl, it piqued my curiosity.

The compositions on The Blue of Distance are hard to classify; arranged parts for the violin, the clarinet and the oboe are merged into throbbing modular synths and warped field recordings of the water underneath a frozen Lake Superior. Saxl herself, as you will read below, isn’t too sure about the ambient label herself either. What is evident is that this music derives from the abstract, from very primal emotions that could be expressed only in this most unconventional structure. It’s a pulsating and restless album, one that, even though it’s so meticulously arranged, seems to hardly have a clue where it is going.

It’s an album in a crossfire of dreams, memories and everyday thoughts, where nostalgia is more distressing than it is joyful; the product of a bleak and lonely winter that followed a warm and worriless summer. The deep water underneath the ice that Saxl recorded for this album may as well be her memory – accessible, sure, but covered with 30 centimetres of solid ice; colder and darker than she had left it. Trying to regain some sense of the ecstasy she felt during what was one of the happiest times of her life, became an exercise that led to The Blue of Distance.

It’s no lockdown record, like Cicada Waves, but came together mostly before the pandemic hit. Its underlying sentiments – feeling far away from what once brought you happiness, unsure how to get it back – are universal, and I could have related to them to an extent in any other year. Yet the distance had never felt so large as it felt in the first five months of 2021, having been in lockdown for an eternity and with hardly an end in sight. For me, listening to The Blue of Distance meant acknowledging that and, through Saxl’s beautifully textured compositions, seeking some sort of solace. ‘Wave II’ stands out especially, with the first thirty seconds sounding like someone submerged in a frozen lake desperately clawing for an opening. All over, there’s glimpses of beauty and joy, but they are faint and hard to catch.

Describing how dark and distressing an album is and turning that into a positive – it’s incredibly difficult. But I have come to realize that just playing sounds and hearing your own exact feelings in them, however depressed they are, is a source of tremendous comfort as well.

Can you take me to the places where The Blue of Distance came together? How do you think those places may have seeped into the music?

“The album was written over a year in two distinct places: I wrote the first half in the Adirondack Mountains in northern New York state. I was in a place called Blue Mountain, it was summer, everything was green and wet, I was surrounded by people who made me feel loved, and I felt quite ecstatic. I wrote the second half many months later in the middle of winter on Madeline Island, an island in Lake Superior off the coast of northern Wisconsin. I was surrounded by ice and snow, I was in a pretty low place, and I felt quite lonely. The album ended up being a record of my attempts to access the feeling of being in a place and time that you are not in currently. I looked at photographs and videos of my summer and tried to remember what it felt like to be there. It didn’t work. It increased the longing. Eventually I made friends with the longing.

So the places very much influenced the sounds, but also the failed attempts to access another place influenced the sounds. Also, the album is built around processed recordings of wind and water from both places, so on a very literal and physical level, the places are in the music.”

Was it a healing process, or a form of therapy, making this album?

“Yes, definitely. A lot of making the album was quite painful and not very enjoyable because I was trying so desperately to get back to a place, time, and feeling that had passed. I was also very confused about where I wanted to be (in many senses), and that confusion was total agony. Eventually, through the process of making the music, I realized that tension between places and identities just is who I am, and that the way to soften the pain was to become friends with the tension and longing and fully feel and accept its shape and form.”

You’re interested in “humanity’s changing relationship with land through new technology”; to what extent did making this album, and the technology you applied (warped field recordings, modular synths, etc.) with nature?

“It highlighted for me just how impossible it is to ever fully reach a distant place, person, or feeling. We can get increasingly closer through improvements in technology, but we don’t seem to be able to ever actually get there. It made me more aware and accepting of how specific my generation’s experience with land and technology is. I think there’s like a 5-year window of people who really came of age at the exact same time as the internet, and that’s a strange place to be. We’re young enough to be comfortable having all this technology fully integrated into our lives, but we’re also old enough to hold onto a fair amount of scepticism. We have memories of both worlds, and that creates a certain tension in us.”

You went into this album with a concept in mind; to what extent did the presence and the fickleness of nature alter the course you had set out for this album’s creation process?

“I’d say the album changed more as a result of my own life getting in the way. I started with an abstract conceptual idea, and then I was overcome with real events in my life and emotions that I couldn’t just push aside. But I think the epiphany was realizing that the issues in my own life inherently mirrored the larger concepts I’d wanted to think about because I am a human living through this specific time and grappling with how technology is changing me. So maybe the lesson was that no matter how abstract you think you’re going, it will always be personal.”

For me, my love for ambient music was enhanced by the first lockdown last year, when the lack of structure, the quiet intensity and the spaciousness of it all suddenly aligned with my day-to-day life. I’m curious as to whether you experienced ambient music differently this last year; and also, if there was a specific moment or experience you remember that made you fall in love with ambient music?

“To be honest, I don’t really listen to much ambient music. I’m actually not entirely certain I even know what it is! This past year, I’ve found I really crave things with easy access points: groove, hooks, melodies. Been listening to a lot of Dua Lipa, Haim, Christine and the Queens, Amber Mark, Tyler, The Creator, and Rosalía. I don’t know why that is – maybe life has felt challenging enough as is, that I just needed some easy music. I do have a very specific memory of the first time I felt overcome by repeating and slowly shifting music, and that was listening to ‘Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices and Organ’ by Steve Reich. It was a completely physical and sensual experience. I had never felt that with music before.”

Finally: are there any ambient records that have impacted you or have had a healing effect on you, that you would like to recommend?

“I’m not sure if these are ambient, but The Wind in High Places by John Luther Adams, ‘Almost All the Time’ by David Lang, ‘Pushpulling’ by Donnacha Dennehy, ‘Panorama’ by Big Dog Little Dog, and ‘Entr’acte’ and ‘Ritornello’ by Caroline Shaw are all somewhat slow moving, deep groove pieces that have made me feel some very big things. Lately, I’ve been really loving The Sacrificial Code by Kali Malone.”

3. Green-House – Music for Living Spaces

The last year and a half brought me onto a lot of existential questions and deeply ingrained mental issues that required solving urgently – or so I would often think. Because what I also learned is that I have the tendency to be overly rigorous and dramatic, and that perhaps I should be setting more achievable goals, making only minor changes in my day-to-day life, and gradually working towards a healthier state of living.

Believe it or not, it’s albums like Green-House’s Music for Living Spaces that made that possible, as well as their EP that preceded it, Six Songs for Invisible Gardens. I would listen to them alongside genre classics like Mort Garson’s Mother Earth’s Plantasia, Hiroshi Yoshimura’s GREEN and a compilation issued by Light in the Attic a few years ago called Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980-1990. All of them perpetuated this conception of music as something to “supplement the environment in which it exists and bring out more of its latent character”. Or in the words of Satoshi Ashikawa, one of the earliest flagbearers for ambient music in Japan, it’s “music that should drift like smoke”.

There was a time where said music, preoccupied as it was with the metaphysical, the act of blending in, rather than standing out, would be easily ignored, filed under ‘new age’, ‘muzak’ or whatever denotation would deny their merit. But that’s not the time of Olive Ardizoni, or Green-House, whose music is not only immensely joyous and comforting, but also builds on the same auditory environmental awareness pioneered by Garson, Yoshimura and others. Music for Living Spaces, especially, stimulates an increased awareness of one’s surroundings (natural or not) and uses it as a path towards self-betterment. Self-betterment, in turn, will only further enrich the world around you, is Ardizoni’s thinking.

There’s a sense of homeliness and childlike wonder to many of these compositions that make improving oneself and one’s surroundings so much more attainable. Here, nature is not all that dramatic and health and happiness can simply be drawn from the ‘Nocturnal Bloom’ of a flower in your back garden or the ‘Royal Fern’ by your neighbourhood pond. It’s an album that sounds small too, serving as an antithesis to any laid out guidance or grand solutions one might seek. Perhaps it doesn’t so much “drift like smoke” but flurry like a first hint of spring through an open window, a modest foundation for better times.

Can you take me to the place where Music for Living Spaces came together? What was the setting like, and how do you think it may have seeped into the music?

“I wrote, recorded, and mixed the album in my small apartment in Los Angeles. I gathered inspiration from taking walks in the park near my house to interact with plant and animal life. The album is very much a reflection of living in a city.”

Part of this album is about relating to nature even when we’re separated from it, like within the confines of our own homes. What are ways in which you guarantee that connection to nature – in your personal life and in your music?

“I do not believe that we are ever separated from nature. That’s not possible because we are nature. I think that the more some of us realize that, the more we will focus on acting in ways that are less damaging to the rest of the environment. I wrote this album in hopes to facilitate meditation on our own nature. Having said that, I definitely keep houseplants and go hiking as often as I can to stay grounded, happy, and connected. If I can’t go outside I listen to nature sounds at home while I do movement based practices.”

What do you think is so important about maintaining that connection to nature? And how did you experience that connection over the last year, as we were forced to stay within our homes for so long?

“Maintaining that connection to nature is staying connected to ourselves. Anything that we do to prioritize our own physical and mental well-being often ends up being in alignment with the health of the planet. Being forced to stay within my home last year gave me the opportunity to reflect on my own health and how to utilize my own gifts to spread empathy and kindness to my community.”

The title of the album implies that it’s intended to enrich people’s everyday environments; in what way do you hope this album can add value to people’s lives or direct environment?

“I hope that this music is useful for people when they want something soothing in the background or when they want to engage in deep listening for meditation. I also hope that it brings people joy!”

For me, my love for ambient music was enhanced by the first lockdown last year, when the lack of structure, the quiet intensity and the spaciousness of it all suddenly aligned with my day-to-day life. I’m curious as to whether you experienced ambient music differently this last year; and also, if there was a specific moment or experience you remember that made you fall in love with ambient music?

“I fell in love with ambient music years ago when I was introduced to Brian Eno’s Music for Airports. It really changed the way that I think about music and it felt very much in alignment with how I experience gender and wanting to live as a person without the constraints of hierarchical structures. Ambient as a medium feels unencumbered by any particular structure so there’s a sense of freedom in composing this type of music.

During the pandemic I did find myself craving songs with a bit more of a traditional structure. My aim on Music for Living Spaces was to combine ambient style with songs that have also more of a story arch. This is still heavily inspired by Japanese environmental music and Erik Satie. I also felt very inspired by Beverly Glenn-Copeland this past year.”

Finally: are there any ambient records that have impacted you or have had a healing effect on you, that you would like to recommend?

“Beverly Glenn-Copeland’s Keyboard Fantasies, David Casper’s Hear and be Yonder, David Hyke and the Harmonic Choir’s Hearing Solar Winds, obviously Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Green and Music for Nine Postcards, Midori Takada’s Through the Looking Glass, INOYAMALAND’s DANZINDAN-POJIDON, Anything Enya has done, anything Laraaji has done, and lastly my favourite: Haruomi Hosono! Particularly Watering a Flower, Paradise View, and Pacific even though I love all of his work. I also highly recommend listening to just nature sounds.”

Epilogue

As I’m writing these closing words, it’s mid-August. Daily life is slowly inching towards a state of relative normalcy. Normalcy meaning: less and less lockdown measures in place, less anxiety in public places, something of a perspective. Other than that, I can hardly remember normalcy - it's been so long. And I don’t think I want to go back to whatever that was either. The last year and a half have been hell, but has also given me things, shown me new insights, very much aided by the aforementioned sounds. And even though I’ve recently found myself longing for the melodious joy of country music, the immediacy of pop music more so than quiet contemplation and blissful nothingness of ambient, I am keen to take these new sounds with me going forward, and more. Gia Margaret’s Mia Gargaret, J.T. Boogaard & R.M. van der Meulen’s PLACE, iu takahashi’s Depthscape, Claire Rousay’s a softer focus, Karima Walker’s Waking the Dreaming Body, Pauline Anne Strom’s Angel Tears in Sunlight, Sarah Davachi’s Cantus, Descant - I can’t end this messy but genuinely very cathartic exploration of my newfound love of ambient music without acknowledging all these new releases and their impact on me. Go listen to their music and support them; they might just do the same for you